It’s Time to Embrace Our EV Future

Original article published here

*note, article title was amended by the editor

As electric vehicles become increasingly popular, a fierce debate rages on the internet with trolls talking trash about electric vehicles and their sudden surge in popularity. The usual points brought up have to do with range and charging infrastructure (or lack thereof). But today, right here and now, I am going to give you scientific and empirical evidence why EVs should and will take over.

The pros and cons of EVs are generally pretty well known — instant torque and cheaper running costs being pros, while the biggest con (and the reason why people haven’t all shifted over yet) is range. Those who have driven an EV, whether they enjoyed the experience or not, will attest to the efficacy of an electric powertrain. There’s just nothing quite like the feeling of 100% available torque at 0 rpm. It’s almost like the feeling of using launch control at every stoplight (maybe more so in a Tesla vs a Nissan LEAF).

Simplicity conquers all

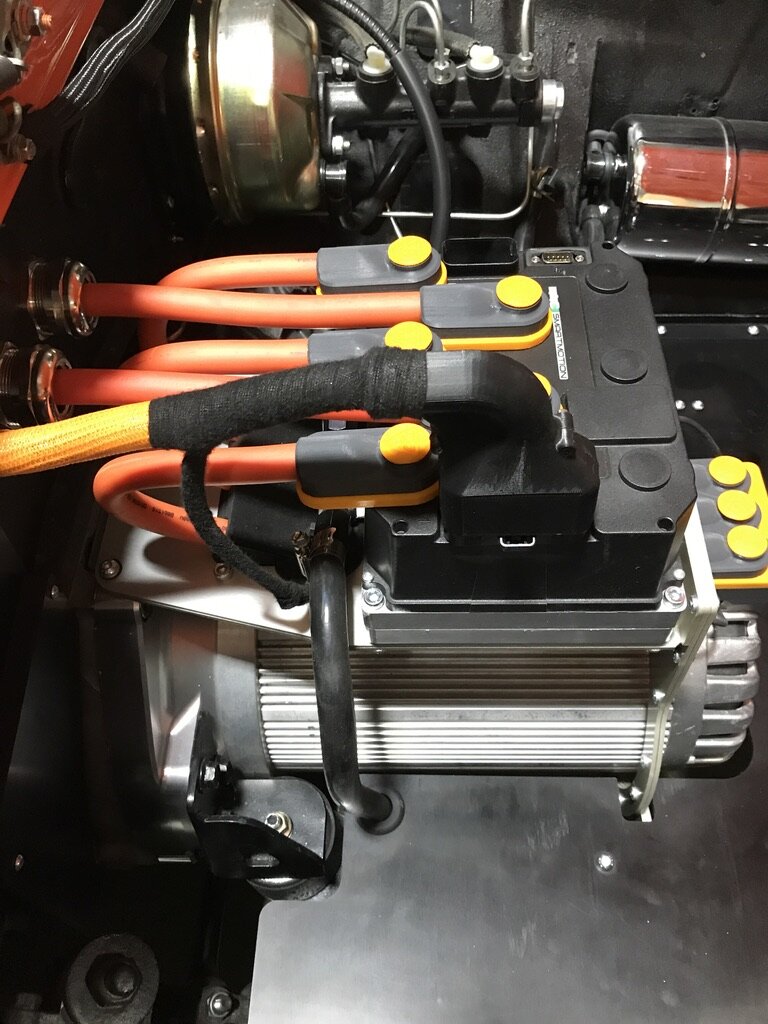

When it comes right down to it, the biggest advantage is the fact that mechanically speaking, EVs are extremely simple. If you include suspension and brake bits, the average EV has 24 moving parts. The fewer moving parts, the longer a product’s usable life should be.

Contrast that with internal combustion engine vehicles, which are fascinatingly complex. On average, they have 149 moving parts. Additionally, many of the pieces we consider “normal” in an internal combustion car only exist due to existing limitations. These items contribute to maintenance being about 40% higher. Have you ever wondered, “why do cars even have transmissions?”

The transmission was very intelligently designed as a way to ensure that engines always operated within their ideal conditions depending on what is being asked of them. This isn’t the only piece of a gasoline-powered vehicle that this logic can apply to. Consider why an engine has oil in the first place: to counteract the friction that occurs with all the moving metal parts. In order for them to achieve sale-able performance figures, several of these systems are considered common on traditional vehicles, yet they ultimately contribute to the increasing cost of a new car.

EV development only became “mainstream” within the last 25 years.

These limitations also contribute to the overall energy efficiency of a vehicle, which is really the only statistic that should matter, now that EV ranges are catching up to the driving ranges of combustion cars. According to the US Department of Energy, “EVs convert about 59%–62% of the electrical energy from the grid to power at the wheels. Conventional gasoline vehicles only convert about 17%–21% of the energy stored in gasoline to power at the wheels.” That’s a pretty dramatic difference in energy inefficiency.

Money matters

What’s also strange is how we’ve come to accept that it is necessary to continually spend money to maintain our cars. So much so, that the industry to keep our cars going is greater than the new car industry itself. In 2016, 6.9M passenger cars were sold in the US, at an average purchase price of $33,000, equaling a $227B year in sales. The average cost for motor oil changes and filling your gas tank is roughly $1,900 a year. With 225M drivers in the US, that equates to about $427.5B spent on just keeping these cars moving (from nonrenewable sources). This isn’t even factoring in all of the independent repair shops that exist that perform other fixes like suspension bushing and accessory repair. Somehow, we’ve let it slip under our noses that the upkeep industry is even greater than the car industry.

While the buy-in price of an EV is, on average, slightly more expensive than the average gasoline car, it’s important to remember the respective timelines of development. Internal combustion-engined cars have had continuous design and development for well over a century. Their supply chain processes have been honed, and their technology has advanced immensely during the technological revolution.

EV development only became “mainstream” within the last 25 years. Their ranges and buy-in prices are almost equal to that of gasoline cars. Imagine if EVs had the same century to gestate. Where would battery technology be? Would we be driving 1,000-mile rage EVs by now?

I’m an enthusiast too

Now, all of this doesn’t mean that I want to rid the world of gasoline-powered vehicles. I happen to own two of them. Two that are inefficient when compared to their newer counterparts. I still find joy in shifting gears, and hearing an exhaust burble as a crisp breeze floats its way through open windows. I’m a car enthusiast.

We need to pressure carmakers to return back to the “less is more” period of manufacturing.

What I want to rid the world of is the idea that igniting a flammable liquid to move hundreds of pounds of metal parts in order to turn a shaft so that I, along with 3 other empty comfortable seats and a large stereo system and plastic cladding, can go to Trader Joes to buy 2 bags of groceries is normal. Perhaps it’s the run-on sentence, but something about that premise just isn’t right. It simply doesn’t seem practical or necessary.

Notice that I haven’t mentioned climate change or global warming once during this piece. While that surely could also contribute solid reasoning as to why we need to phase out of using combustion-engined cars in our city centers, I don’t see it as the most damning evidence supporting the adoption of EVs.

If there’s anything that’s to take away from this, it’s that we need to pressure carmakers to return to the “less is more” period of manufacturing. Even if this methodology is applied to traditional gasoline-powered cars, we’d be better off. Hell, my 23-year-old BMW 3 Series gets almost the same gas mileage as a brand new 3 series, and I don’t have to leave the house any earlier to get to a meeting than would the owner of a new 3 Series.

Less is more. Most EVs are just that — less. Less moving parts, less inefficiency, less costly to maintain (I realize that should be “fewer” but then it is less poetic). Put together, that makes them so much more than gasoline cars.